The future generation insists on being heard regarding climate change

Science Writer S. Ananthanarayanan points up the generation gap, and the conflict of interests between older and younger age groups, in terms of the cost-benefit ratio of climate change action.

By S. Ananthanarayanan

Steps to contain global warming, mitigate climate change, and move to greener lifestyles are not without their costs. The payback is of course radical – a more habitable and safer world. However, does the cost-benefit ratio differ according to one’s age bracket?

The costs and benefits of climate change mitigation are not the same for all countries. But are they higher for younger people than for older ones? And does the ratio differ in different parts of the world?

Haozhe Yang and Sangwon Suh, from the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California, Santa Barbara, look into these questions in a paper in the journal, Nature Communications. And an editorial in the journal Nature reports that “young people will be key” at the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26) to the UN climate convention taking place in Glasgow, Scotland on 31 October 2021.

COP26 in Glasgow – Young People will be key

“The world’s youth movements are following the science of climate change… and COP26 would be wise to involve them in decisions”, the editorial in Nature Journal says.

The Nature paper seeks to substantiate the belief that younger people have a larger stake. “A prevailing narrative,” the paper says, “is that younger and future generations are the greatest victims of climate change driven by the actions and inactions of older generations.”

While younger people should benefit most by mitigating climate change, there is “no peer-reviewed literature that quantifies the costs and benefits of climate change mitigation by age cohorts at a country level,” the Nature paper continues.

Measures to contain Global Warming and Costs

Containment of global warming calls for several measures. One is less use of fossil fuels and energy and others are changes in land use, agriculture, housing, and services. These changes in economic systems would affect all sectors and lead to a reduction of the GDP of nations.

In deriving the overall cost of measures to mitigate global warming, as called for by the Paris Agreement, the Nature Communications paper relies on Integrated Assessment Models, developed by research groups and adopted by the 2014 report of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). According to the Nature Communications paper, the cost works out at between 2% and 6% of the global GDP, up until the year 2100.

The benefit of incurring this cost would be in avoiding the economic damage of temperature rise. The paper cites a 2015 study that said the productivity of states peaks at an average annual temperature of 15°C, and then there is a pattern of fall in productivity as temperature rises. On this basis, the study estimated that “keeping the global temperature at the 2010 level could save 23% of global GDP by the year 2100.”

Losses would dominate the early years

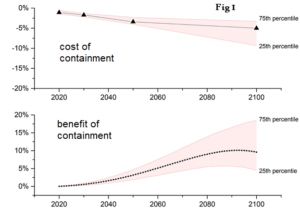

What the estimates indicate is that while there would be losses due to the costs of keeping global warming down, and these would dominate the early years, the saving of the greater economic loss that higher temperature would cause in later years, if warming were not contained, would result in a net gain. Figure 1 shows the way the figures change, with benefits rising as the years advance, to compensate costs.

What the estimates indicate is that while there would be losses due to the costs of keeping global warming down, and these would dominate the early years, the saving of the greater economic loss that higher temperature would cause in later years, if warming were not contained, would result in a net gain. Figure 1 shows the way the figures change, with benefits rising as the years advance, to compensate costs.

Conflict of interest between older and younger

What the study has not considered, the Nature Communications paper says, is how these costs and benefits accrue to different age groups in different parts of the world. We can see that older people, at the start of the 2020 to 2100 period, would bear higher costs but reap lower benefits, within their lifetime. In contrast, younger people would benefit from lower temperatures in later years, as compared to the ‘no mitigation and no loss in earlier years’ scenario. There is hence a conflict of interests between the older and younger lot when valuing current investments to contain global warming.

Losers and Gainers

In order to quantify the relative interest of persons of different age groups, the authors calculated the cumulative cost-to-benefit difference, per capita, with the numbers pertaining to later years discounted to the base year at the rate of 3% per annum. The cost-benefit of each year over the lifetime of a person was hence reduced to its value at the base year, and the lifetime cost or benefit was the total of each year’s discounted figure. This was done for different age groups of persons born between 1920 and 2020, and separately for 169 countries.

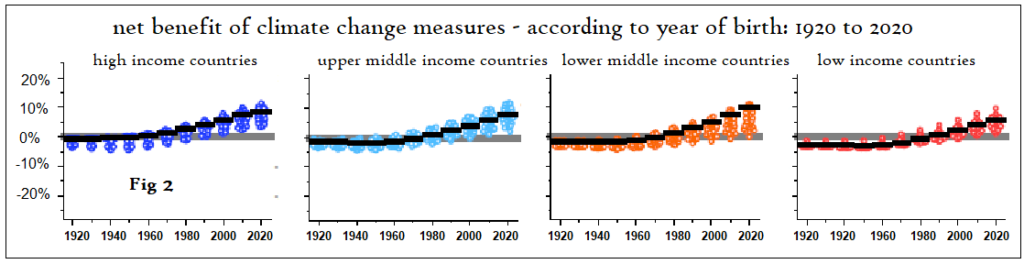

Some of the findings are shown in Fig 2, that the year 1960 is the cut-off in high-income countries and those born before would face a net loss as a result of climate change mitigation, while those born after 1960 would be gainers. In lower-income countries, the year is later – 1980.

The cut-off year itself is variable, according to the form of the model, and circumstances, e.g. in countries in the north, warming would lead to savings in heating costs. But the message is that younger groups are the ones that would most benefit, in terms of less hardship, as a result of climate change mitigation.

“Age cohorts born prior to 1960 generally experience a net reduction in lifetime gross domestic product per capita. Age cohorts born after 1990 will gain net benefits from climate change mitigation in most of the lower-income countries. However, no age cohorts enjoy net benefits regardless of the birth year in many higher-income countries,” the paper says.

Glasgow meeting, 1-12 November 2021

The editorial in Nature is about the Glasgow meeting, 1-12 Nov 2021, where countries report their compliance with commitments made in 2015. While there has been progress in some sectors, like fossil fuel replacement, it is clear that we need policies with a wider reach: “a revolution in how economies are run, and in the choices world leaders must make,” the editorial says.

In the 2015 meeting, countries agreed to review their targets to match the latest assessments, every five years.

“Forty-eight countries — including major emitters — are yet to set new targets, and some clearly have no plans to accelerate their climate ambitions,” the editorial says.

Again, in Copenhagen in 2009, the richer countries agreed to provide US$100 billion per year to less wealthy nations by 2020, a promise that is far from being kept.

Climate laggards will be called out by the new generation

At Glasgow, the new generation of climate researchers and campaigners is expected to “call out climate laggards and countries that are not fulfilling their funding pledges”.

For the first time, the editorial says, the “future generation” is more than words in policy statements – the generation is here and insists on being heard. In the context, the study by Haozhe Yang and Sangwon Suh underlines the clash of economic interests that is involved and suggests a way forward.

“Closing the economic disparity among age cohorts may require different climate policies to different age cohorts. The increase in renewable asset price may alleviate the intergenerational disparity under climate change mitigation, given that different age cohorts hold varying amounts of renewable assets. Our study shows that the cost-benefit distribution among age cohorts can be an important consideration for policymakers when designing tax and fiscal policies in response to climate change mitigation,” the study says.

You can reach the writer S. Ananthanarayanan at response@simplescience.in