Dr Brian Fleming commenced a study, early in 2019, to explore the level of resources needed to tackle the challenges facing DEIS schools. This study was supported by NAPD, CEIST, The Jesuit Provincialate, and Le Chéile.

—By Dr Brian Fleming

Dr Brian Fleming, School of Education, University College Dublin.

The DEIS programme (Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools) was launched in 2005. By comparison with previous efforts to tackle educational disadvantage, it contained a number of improvements. Various initiatives, introduced over the years, were brought together in one strategy. An objective mechanism was devised to determine which schools were entitled to participate and benefit from the scheme. Finally, ongoing evaluation by the Education Research Centre was built in from the start.

The absence of a control group makes it impossible to draw specific conclusions about the impact of DEIS but it seems progress is being made, under a number of headings, albeit at a slow rate. In 2015, the ESRI issued a comprehensive report entitled Learning from the Evaluation of DEIS. Perhaps the most fundamental point made in this report was that little discussion had taken place about the level of resources needed by DEIS schools to tackle the challenges they are facing. Hence my study, commenced in 2019 and supported by NAPD, CEIST, The Jesuit Provincialate, and Le Chéile, to explore the level of resources that schools needed to tackle the challenges facing them.

There are almost 740 post-primary schools in total, of which about 200 are in the DEIS programme. So, a letter was sent to a random selection of fifty DEIS schools seeking participants to become involved in a case study. A generous response enabled me to select six in such a way as to reflect the most obvious contextual factors. Interviews were undertaken with forty-three teachers in the schools, including classroom teachers, year heads, guidance counsellors, HSCLs and principals. Focus group discussions were held with senior students (n=29) and parents/guardians (n=41). In addition, twenty-eight educationalists, not connected to the six schools, were interviewed to gain their insights and experiences. A huge range of matters arose during this research. In this piece, however, I will focus mainly on the resources issue.

Grades of disadvantage

It is trite to say that all schools are different but this is, in fact, the case. The nature of the catchment area, traditions, culture, ethos and the balance of student intake, all contribute to this reality. DEIS schools, in general, experience additional classroom and organisational challenges when compared to their peers in more mainstream settings. In addition, DEIS schools are different from each other. There are grades of disadvantage. Indeed, having spent three or four days in each of the schools, this was obvious.

From the start, the DES recognised this reality at primary level by designing the DEIS scheme with three levels. No reason has been advanced as to why the situation should be different at post-primary level, yet, fifteen years later, this issue has not been addressed. While it would be unrealistic to expect the DES to implement a bespoke arrangement to respond to the individual needs of every school, something a good deal more precise than the current arrangement is needed.

DEIS and non-DEIS

The more fundamental difference, of course, is the difference between DEIS and non-DEIS schools. The mere existence of the DEIS programme recognises that reality. The six schools, while different in some respects, shared a number of common features:

In these circumstances, the challenges facing those who work in DEIS schools are far greater than the norm. The pressure on school leaders has increased significantly in the last decade at the same time as resources were reduced. While this is true of all schools, the nature of the working environment in DEIS schools means that principals and their deputies cannot devote significant time to their leadership role.

The DEIS programme’s response to these additional organisational and educational needs is extremely limited. With the exception of one ex-quota HSCL and a somewhat higher guidance allocation, the system for determining a school’s entitlement to staff members who hold specialised roles such as deputy principals, assistant principals, and year heads is based solely on pupil enrolment and takes no account of need. As a result, the needs of the disadvantaged are not being met.

Within the state-funded sector, we have a two-tier education system. It is not just that the total resources devoted to education are inadequate, though they are, but the mechanisms in place are such that the gap between the disadvantaged and their peers will never be closed.

A serious objective?

The Education Act (1998) commits the state ‘to promote equality of access to and participation in education.’ Looking back over the last quarter-century, one is entitled to ask whether the policymakers, both political and administrative, are serious about achieving this objective.

It is fine to say that progress is being made, yet cohorts of young people are not being enabled to reach their full potential. This policy failure has serious consequences both for the individuals involved and for society generally.

One striking feature is the facility with which the DES established expert groups and then ignored the findings and recommendations. Four important reports fell into that category: Blackstock (1999, on a fair & transparent school funding system), Martin (1997 & 2006, on a multi-disciplinary support service for schools) and McGuiness (2001, on teacher allocations). All proposed strategies would have made a significant difference to the disadvantaged but they were not implemented.

The DEIS programme meanwhile was not updated until 2017 even though ongoing evaluation is part of the process. The 2017 version included a list of objectives to be achieved on or before 2020. Therefore, an updated version is now due. While COVID may have interrupted the process, it is striking that the Programme for Government contains only one minor reference to DEIS and no commitment to review it.

Two recommendations

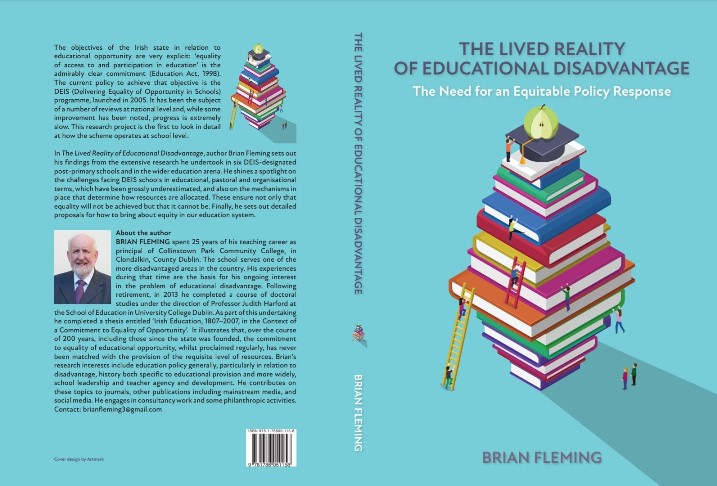

The research project on which this blog is based has been published as The Lived Reality of Educational Disadvantage. It contains sixteen policy recommendations based on the insights and observations of all the participants who gave so generously of their time and expertise. In the space available, I will outline a summary of the first two: