There is a ‘moreness’ about nature that science does not explore

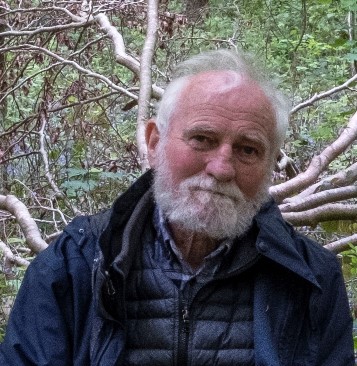

—by Paddy Madden EdD

Dr Paddy Madden is a former primary teacher, an author, a lecturer in social, environmental and scientific education, and a Heritage in School specialist since 1999. He visits schools regularly to engage children with nature.

Nature education undoubtedly has scientific and geographical elements incorporated in it. What is the function of the root of a plant? How is a worm adapted to its environment? What conditions does a seed need to germinate? How is rock formed?

The scientific approach is the one advocated by the designers of the revised primary curriculum and by the inspectorate which monitors its implementation in schools. However, a scientific approach to engaging with nature is not an umbrella for all the potential learning that children can garner from engagement with the natural world. An alternative view is this one: there is a ‘moreness’ about nature that science does not explore.

‘Moreness’

This ‘moreness’ incorporates the development of creativity, cultural awareness, spirituality, cognitive abilities: mental and physical health, mindfulness, and caring qualities in both children and adults. It worked in reducing significantly the impact of Covid-19 on peoples’ lives and many people have confirmed that engagement with the natural world has contributed greatly to their mental and physical wellbeing in a time of uncertainty and anxiety. These people have been able to divert their attention from the crisis by being mindful in nature on their daily walks or working in the garden amongst their plants.

‘Soft Fascination’

They were in fact utilising the Attention Restorative Theory (ART), which was formulated by Stephen and Rachel Kaplan in the USA in the 1980s. The Kaplans concluded that intense directed attention causes great fatigue after a while, but this fatigue can be relieved by a process entitled “soft fascination”. They found that nature was effective in providing this involuntary attention or soft fascination, and restoration was generated by the lowering of fatigue, which was initially caused by directed attention.

The poet Robert Frost, in his poem Dust of Snow, demonstrated this theory in practice too. A moment of fascination in nature is encountered when a crow shook some snow from a hemlock tree. This event caused him to have “A change of mood/And saved some part/Of a day I had rued”.

Importance of bonding with the natural world

In order to promote their holistic development, children need to be exposed to nature and educated about it in a meaningful way so that they form a life-long attachment to it and, as a result of this attachment, they seek at all times to protect it. “What is important is that children have the opportunity to bond with the natural world, to learn to love it, before being asked to heal its wounds” (David Sobel). This is a profound statement from one of the world’s leading environmentalists. He is asking educators not to focus on the gloom and doom scenario relating to planet health such as climate change when they are teaching their students, but instead to adopt a positive approach with them in their engagement with the natural world.

Back in 2008, Sir David Attenborough said, “Nobody is going to protect the natural world unless they understand it”. If Attenborough is correct, then the stark fact that this natural world has lost 60% of its mammals, birds, reptiles, and reptile species in the past fifty years will mean little to young people who have had minimal exposure to the natural world, particularly in outdoor settings. Their lack of knowledge will have huge negative implications for the preservation of species and habitats.

In the report, Noticing Nature: The first in the Everyone Needs Nature series (2020), the National Trust in association with the University of Derby, found that “noticing nature in small, everyday ways could lead to radical results”, such as generating conservation action and enhancing wellbeing.

Richard Louv, who wrote the seminal book Last Child in the Woods, has quite a lot to say about the negative influence of the over-preoccupation of students with digital technology and the way that this affects their cognitive, mental, physical, and social development. He concluded that ‘the more high-tech we become, the more nature we need’.

Nature in the Primary School system

If contact with nature is so important for our wellbeing, cognitive development, and planetary care, how is nature education faring in our primary school system? In 2014, I set out on a research journey to explore the state and status of nature awareness, appreciation, and education in the Irish primary system. I discovered that input into all of these strands of nature education could be improved. Reasons for the lack of robustness in this sphere of education, put forward by teachers and environmentalists, were varied. They included an overcrowded curriculum; a lack of knowledge; health and safety concerns; an over-emphasis on the physical sciences; a lack of preparedness for engaging with nature in the Colleges of Education and in CPD courses; and poor design of school grounds.

Gauging Student Teachers’ Knowledge of Nature

I examined a representative sample of first-year student teachers to determine their knowledge of the sixth class nature syllabus which most of them had encountered five-to-six years earlier. Findings from the questionnaire administered to them demonstrated that they had limited knowledge about the workings of the natural world in general.

Only a few (less than 14%) could identify common birds and butterflies and indicate the reason for ladybirds hibernating during the winter.

A similar number could not classify molluscs and crustaceans, name the five species of vertebrates, differentiate between reptiles and amphibians, or construct a seven-part food chain.

A small number (15-24 percent) could identify common tree fruits and buds and indicate that porpoises, whales, and dolphins are mammals. Less than half (25-49 percent) could explain why flowering plants produce nectar, the reason why a spider is not an insect, and two reasons why worms are beneficial to the soil.

Only, 43 percent of the students could identify an oak leaf in a multiple-choice question. This is arguably the most identifiable leaf of all trees with its distinctive shape and lobed margin.

It is of interest to note that the majority of the students (7 percent) who participated in the questionnaire had studied biology up to Leaving Cert level. Fifty-per-cent had studied Geography to this level.

One gathers from the answers given by the students that they had considerable difficulties with the concept of food chains, classification of species, knowledge of habitats, food sources of species, migration, hibernation and conservation techniques, and identification of plants and animals.

Should studying the natural world be a foundational subject in the primary system?

I suggest that it should because presently the Science and Geography syllabi do not adequately address the depth and breadth of the uniqueness of the natural world for enhancing the overall quality of our lives and our learning potential. Changing the study of the natural world to a stand-alone subject would confer status on this aspect of education that is not there at present. This distinction would propel it to a level it deserves in the primary system.

The elevation of nature education within our schools to a higher status has never been more necessary.